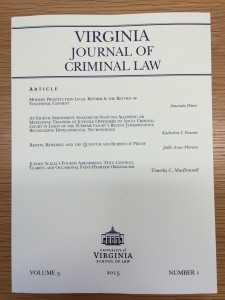

Date of Publication: Spring 2015

Date of Publication: Spring 2015

Articles:

Amanda Peters, Modern Prostitution Legal Reform & the Return of Volitional Consent

Find on Westlaw

Abstract: In the last century, American prostitution laws focused exclusively on contractual consent rather than volitional consent or traditional mens rea. The laws’ failure to distinguish between voluntary and involuntary actors resulted in de facto strict liability charges, trials, and convictions for involuntary actors. Prostitution laws have undergone major reform in the past decade due to human trafficking concerns. As a result, states have enacted prostitution-specific safe harbor, affirmative defense, and expunction statutes designed to protect individuals forced or coerced into committing prostitution. This Article examines the pre-reform contractual nature of consent in prostitution cases, the reform’s return of mens rea to prostitution laws, and the historical underpinnings of volitional consent in prostitution jurisprudence. By distinguishing between individuals who choose to commit prostitution and those who do not, modern prostitution reform does more than merely safeguard against unjust convictions: it restores the element of volitional consent to its rightful place within the crime of prostitution.

Katherine I. Puzone, An Eighth Amendment Analysis of Statutes Allowing or Mandating Transfer of Juvenile Offenders to Adult Criminal Court in Light of the Supreme Court’s Recent Jurisprudence Recognizing Developmental Neuroscience

Find on Westlaw

Introduction: Recent Supreme Court cases have recognized the science underlying the common-sense notion that children are not “little adults.” Their brains function in a completely different manner than those of adults. In 2005, the Court abolished the juvenile death penalty and recognized the neuroscience underlying the claim that those under the age of eighteen should not be subject to the ultimate punishment due to the fundamental immaturity of their brains. Later cases, discussed in depth below, followed similar reasoning in abolishing life without parole for non-homicides for juvenile offenders and in holding that juvenile offenders cannot be subjected to a mandatory life sentence even for homicide. In each of these cases, the Court applied an Eighth Amendment analysis.4 In contrast, cases assessing the constitutionality of procedures employed in juvenile delinquency courts employ the “fundamental fairness” test dictated by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. . . .

(footnotes excluded)

Joëlle Anne Moreno, Rights, Remedies, and the Quantum and Burden of Proof

Find on Westlaw

Abstract: It is tempting to commemorate the 2014 centenary of the exclusionary rule by celebrating our historically progressive role in constitutional rights protection, but those familiar with the facts know that Fourth Amendment violations persist unabated. As New Yorkers consider Judge Scheindlin’s damning assessment of police stop-and-frisk practices, and the country erupts in protests following fatal police encounters, are legal scholars who continue to pontificate on constitutional bona fides addressing “real” Fourth Amendment questions?

Traditional academic abstraction and artificial doctrinal divides obscure the fact that rights and remedies are defined by their operation. Constitutional rights have no value if, after they have been violated, meaningful remedies are unattainable. This Article focuses instead on the functional relationship between rights and remedies and on *90 new constraints imposed by judicial recalibrations of the quantum and burden of remedial proof.

The Roberts Court’s recent shotgun wedding linking exclusion to defense evidence establishing police officer “bad faith” or systemic police negligence illustrates the centrality of proof and evidence questions. Over the past few years, the Court has increased the quantum of defense suppression proof while simultaneously eliminating burden shifting to the prosecution. These shifts make most Fourth Amendment violations irremediable. It is not feasible to demand that defendants aggregate data establishing systemic police negligence. Defendants who seek, in the alternative, to prove that an illegal search was committed knowingly, recklessly, or with gross negligence invariably lack direct evidence of police officer intent. By changing the rules governing suppression under the guise of a narrow focus on deterrence, the Roberts Court has ensured that nearly all illegally seized evidence will be admitted. The only time evidence will be suppressed is when a defendant can prove circumstantially that police misconduct was so patently egregious that defense evidence supports a judicial inference of police “bad faith.”

In theory, the Roberts Court has quietly erased a century of exclusion jurisprudence while eliding accountability for more overt action. In practice, if suppression is only available to defendants who can prove flagrant police “bad faith,” the Court has effectively resurrected the old due process “shocks the conscience” exclusion standard. New decisions illustrating the type of police behavior that can support an inference of bad faith under include patently race-based seizures, near-suspicionless repeated rectal searches, and (in a truly unforgettable case) the curbside excision of contraband from a suspect’s penis performed by the arresting officer.

The full impact of increasing the quantum and reallocating the burden of proof is fully revealed in recent empirical studies demonstrating that illegally seized evidence is now routinely admitted. Prosecutors’ new, easy access to this evidence following warrant-based and warrantless searches will transform not just the small number of cases that go to trial, but plea calculations in every case where evidence was previously excludable on Fourth Amendment grounds.

Timothy C. MacDonnell, Justice Scalia’s Fourth Amendment: Text, Context, Clarity, and Occasional Faint-Hearted Originalism

Find on Westlaw

Abstract: Since joining the United States Supreme Court in 1986, Justice Scalia has been a prominent voice on the Fourth Amendment, having written twenty majority opinions, twelve concurrences, and six dissents on the topic. Under his pen, the Court has altered its test for determining when the Fourth Amendment should apply; provided a vision to address technology’s encroachment on privacy; and articulated the standard for determining whether government officials are entitled to qualified immunity in civil suits involving alleged Fourth Amendment violations. In most of Justice Scalia’s opinions, he has championed an originalist/textualist theory of constitutional interpretation. Based on that theory, he has advocated that the text and context of the Fourth Amendment should govern how the Court interprets most questions of search and seizure law. His Fourth Amendment opinions have also included an emphasis on clear, bright-line rules that can be applied broadly to Fourth Amendment questions. However, there are Fourth Amendment opinions in which Justice Scalia has strayed from his originalist/textualist commitments, particularly in the areas of the special needs doctrine and qualified immunity. This article asserts that Justice Scalia’s non-originalist approach in these spheres threatens the cohesiveness of his Fourth Amendment jurisprudence, and could, if not corrected, unbalance the interpretation of the Fourth Amendment in favor of law enforcement interests.